Echoes

A Liszt concert in September at the Royal Palace of Gödöllő, a favorite of Empress Sissi.

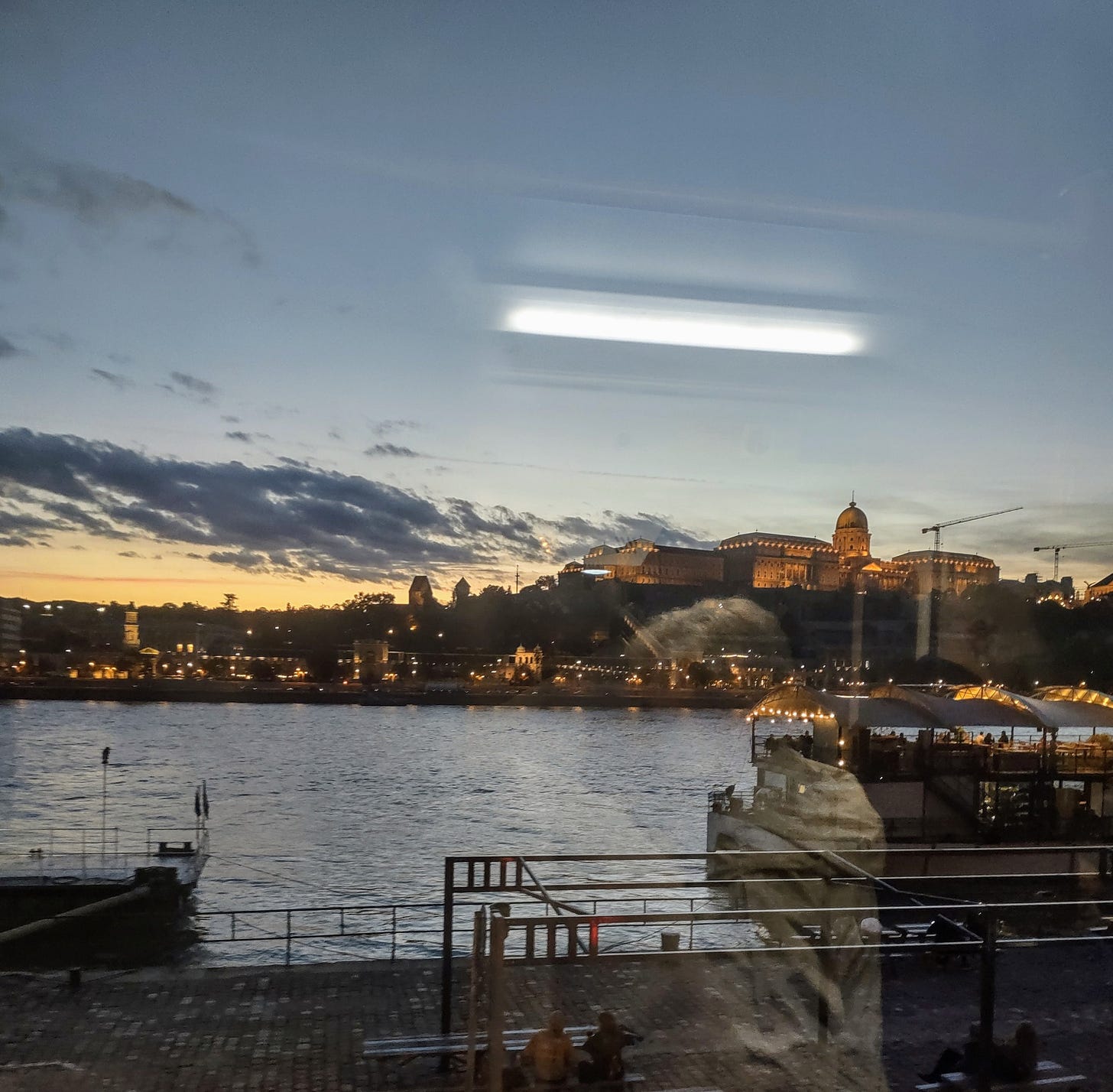

A faded yellow tram runs along the east side of the Danube, thrumming past river boats and bridges on one side, and beautiful old buildings and cobbled streets on the other, and that’s the tram I took as the sun was setting on the river last week. We had tickets for Franz Liszt’s Legend of St. Elizabeth performed by the Hungarian philharmonic orchestra. Decked out in a thrifted dress, gifted shawl, and brand-new shoes, clutching my beaded bag (another thrifted treasure), staring out the windows as we swing along the tracks, hoping my husband got out of work in time to meet me at the concert hall—the kind of thing that people do in books and not in real life.

Watching an orchestra is a mystical experience. The Music started gently, with the fluttering of flutes that we could barely hear perched in the very last row, then catapulted into rippling and receding waves of music.

It's like watching a shadow, an echo, of what creation must have been. Before the music starts, there’s nothing. Chaos. People talking and laughing, shifting in their seats, moving coats and purses, and shuffling programs. The lights dim, silence falls, and then a collective breath. Slowly, something bigger and more beautiful than the sum of all the single instruments played on their own looms into existence. The conductor pulls the music out of his musicians, drawing it out, agonizing over the growing, flowering music, forming it with his careful hands. Musicians labor over their instruments, calling up the years of dedication that they’ve poured into their craft to make the lumps of wood and metal sing. It’s simultaneously a vision of human mastery over creation and a vision of how little mastery we have. The music is more than its constituent parts, and it will outlive us all.

There was a little old woman with white hair, in the third row at center stage, face turned up to the music. I think she’s been listening to orchestras all her life, before her hair turned gray, then still as the tide of time turned and all that had belonged to her youth changed to winter and fell slowly away. But the music would have been the same, music written by a writer long dead and first brought to life by players who have long passed on into anonymity. And the anonymity is fitting, integral even, because it doesn’t really matter who the first violinist is, or who plays the music written for the French horns and the trumpets, or who clangs the cymbals. Even the conductor doesn’t matter in the end. Many musicians have played those parts before and many will do so, many times over, until the end of music or the end of the west or the end of the world.

It's a serious business, stepping on to the stage and playing part of the music. It’s recreation in the deepest sense of the word, a remaking of the men and women picking up the instruments and pouring their hearts and souls through their fingers onto strings and keys. It’s work: effort, sweat, sacrifice, love, all for the sake of cooperating in the creation of something immortal—ephemeral too, because once the music dies away, it’s gone. The right notes fit. One wrong note, and the whole falls apart.

I remember reading—and disliking—Dante’s Paradiso when I read it years back. I should read it again (a point my husband strenuously agrees with, as he takes issue with some of the characterizations that follow, but I digress). Dante described Heaven like a great cosmic dance (harmony, my husband objects), and I felt that that made the saints into nothing but anonymous cogs in a great cosmic wheel. Anonymity in Heaven doesn’t sit well with me (much the way my treatment of Dante doesn’t sit well with my husband, it seems), but I wonder if I just wasn’t looking at it the wrong way round (vigorous nod of agreement). It wasn’t a negation, but a fulfillment, the narrative version of the music (polyphony, he pleads) of Palestrina.[1]

Music pouring out of a violin—where before there had been silence—at the hands of a master violinist is deeply personal, even if the notes fit somehow into the mysterious greater whole. It involves and requires the whole person, invested, sacrificed, poured out, a shadow and an echo again of what it must mean to work out salvation in fear and trembling. Beauty can be an awful thing, and redemption is that way too: mystical, mythical, awful. There can be no half measures in Christianity. The old man must be killed, as was Christ, so the new man can be made. We die when Christ dies.[2] And every day we step onto the stage and take the instruments of our salvation into our hands. Fulton Sheen describes the Mass in those terms too—every sacrifice, every ache, every painful awful moment comes with us to the Mass so that we can become like Christ, the victim and the victor on every altar.

And so I come to the audience, to us, sitting in the dark. Before the music began, the conductor faced us and bowed, as if we were guests of honor. But what had we brought with us? We were hungry and restless. Our seats were uncomfortable. My feet hurt. People around us were whispering and shifting in their seats. And sad to say, it’s difficult to leave the digital world that we’re so accustomed to, without automatically reaching for a phone—just a quick little distraction, a quick text, a quick photo.

Training the heart and soul to be disposed to beauty is not easy. It takes effort and practice to see and appreciate the beautiful, to give the right value response as Von Hildebrand would say, to sit rapt and still like the woman in the third row was. Developing a disposition of the heart takes work, and I’m a child, in that respect, restless, too easily distracted, and too easily satisfied. Great music shows us our littleness, and whispers to us about the beyond. It echoes the music of the cosmos and makes it materialize to give us a glimpse of what lies beyond the distraction and discontent that’s both our daily bread and our daily battle. Mystics and musicians, the great ones at least, can hear the leaves and trees and rocks, crying out the story of creation and salvation, and we’re all called to be mystics as John Paul II tells us. I wonder what he could hear when he listened to the world.

There’s more that’s been created that we don’t have the eyes for yet, more to see and love. Farther ahead, there’s more beyond.

[1] (Apparently this point has been made elsewhere—as I’ve now been told on the most reliable authority that Dante’s comedy has always been described as The Summa in verse. Thomas and Dante—I should have known I was sticking my neck out).

[2] I owe C.S. Lewis a debt of gratitude for the way he described this in Mere Christianity, which I read for the first time in the fall of 2017—his description has stayed with me since.